Entrepreneurial Best Practices from Michelangelo and Leonardo

- Gerriann Brower

- Jan 25, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Jun 18, 2022

Art is a business

The making and selling of art may not be the world’s oldest profession, but it has been a commercial endeavor for thousands of years. Western artists have been independent business people for about 500 years. What can today’s entrepreneurs learn from two of the world’s greatest artists – Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci? Both were internationally successful artists during the Italian Renaissance, each had very different ways of conducting the business of art, and each leave us with relevant lessons for today’s business leaders.

Before looking at what we can learn from them a little context is helpful to understand how they pushed the boundaries of the art business. The Middle Ages art business consisted of craftsmen who excelled in masonry, sculpture, painting, and stained glass and went from town to town looking for clients or commissions. Gothic cathedrals were largely built by master craftsmen, and stonemasons who worked for many years, or a lifetime, on a building project. These men were mostly anonymous. Anonymity did not pay well. Craftsmen were paid about the same as food service workers or potters with low to middle class social status, at best. They were not entrepreneurs, nor were they encouraged to be.

Then came the Renaissance

In the 1400-1500s artists gained more control over contracts and commissions. The Renaissance humanist concept recognizing individuals contributed to artists transitioning from craftsmen to powerful and revered artists. Artists were now independent business persons, in charge of studios, marketing, assistants, finances, obtaining commissions, and keeping patrons satisfied. Two of the most famous Renaissance artists were successful as business persons and deserve a closer look at how their entrepreneurial practices can inform today’s leaders.

Game Changers

Michelangelo became one the most highly paid artists of the1500s. His business success was driven by an intense desire to provide for his family and future generations. He was paid astronomical prices for artwork in his twenties, before painting the Sistine Chapel in Rome. His net lifetime income after taxes and expenses was unprecedented. Michelangelo took a great leap forward in creating a business model for entrepreneurial artists. Not everyone followed, but he was a great investor in real estate, kept careful fiscal records of his debts and credits and was a hard negotiator with patrons, including the popes. Albeit a spendthrift, he died a very, very rich man. He was the first art superstar with international fame.

Leonardo da Vinci, a contemporary of Michelangelo, only completed 14 paintings in his lifetime. Leonardo was driven by perfectionism and problem solving. His many notebooks and scientific inquiry about nature and the human body earned him a reputation for creativity, experimentation, and an endless desire for knowledge. Leonardo, most famous for the Mona Lisa, was also well paid for his art, but was a spender rather than a saver. Although highly sought after by the wealthy elite for artwork and inventions, he died with a very modest sum of money. Leonardo was well regarded as a courtly gentleman who was generous and sociable. A painting attributed to Leonardo recently sold for $450.3 million to a Saudi Prince. Both these artists have not lost status in art or culture for over 500 years.

Best Practices

Besides their technical genius there are some entrepreneurial practices that contributed to their success. There are four key lessons from these game changing art entrepreneurs that today’s business leaders can apply.

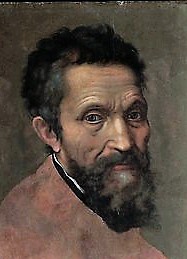

Left: Daniele da Volterra, Portrait of Michelangelo, detail, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Digital image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Open Access Policy, CCO 1.0.

Right: Wincelslaus Hollar, etching of Leonardo da Vinci. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Digital image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Open Access Policy, CCO 1.0.

Financial Management

Michelangelo knew his cost of goods sold: the marble, his tools, paints, assistants, rent for his shop. He kept good records and understood the finance of art. He was essentially the CEO of the largest art company of his time. He minimized labor costs and understood finance from a holistic approach. Today’s entrepreneurs, like Michelangelo, should cultivate a good relationship with their banker and pay close attention to the fiscal health of their company. Entrepreneurs, be a Michelangelo: create a financial management system, learn to read financial statements, create a cash reserve, track business performance and understand financing choices.

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, Louvre, Paris. Public domain, Pixabay.

Collaboration

Collaborative workplaces were commonplace 500 years ago as well as today. Leonardo was keen to share his drawings with other artists and open his studio to them. He was not threatened by competition and was a mentor to others. Michelangelo took the opposite approach and was secretive and did not share with others. By the end of his long career, his style was considered out of date as he would not change the way he painted or take advice easily from others. Collaboration in Leonardo’s circle encouraged new approaches and fostered curiosity. New artists, like entrepreneurs, strengthened their skills by learning from others and sharing challenges and successes. Entrepreneurs can learn much from peers as they recognize their strengths and weaknesses. Rather than fearing competition, artists and businesses can leverage competitiveness to focus their products and services.

Quality Control

The basic concept of quality management isn’t drastically different from 500 years ago. Business leaders must be attentive to the quality of their products and services. Quality encompasses customer service, staffing, materials, workflow process, training and knowledge of customer needs. Michelangelo went to the mountain to hand select the marble and accompany it from the mountain to the studio, to avoid any mishaps that would damage the stone. Leonardo worked on the Mona Lisa and other paintings for years, and set high standards for all aspects of his art from drawings to finished products. Future commissions could be endangered if they didn’t deliver a high-quality product to their patron. A customer centered approach is as essential to a business today as in Leonardo’s time.

Michelangelo, Sistine Ceiling, Vatican, Rome. Public domain, Pixabay.

Get Outside Your Comfort Zone

Business leaders need to constantly innovate in rapidly changing market places. Sometimes this means changing your product or service to adapt to customer needs or wants or reacting to an unforeseen challenge. Michelangelo, against his will, was commanded to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling by Pope Julius II. He thought of himself as a sculptor, not a painter. Previously he had completed a 47-inch diameter painting. The Sistine ceiling is 5,754 square feet. He made mistakes along the way, especially in scaling up to such large dimensions, but rose to the occasion. Being uncomfortable with new challenges led Michelangelo to new innovations. Embrace novelty; don’t always stick to what you know.

If Leonardo and Michelangelo could speak to business leaders today, I believe their advice would boil down to one thing - do what you love. Their success grew from their passion for creating art. Their accomplishments, for entrepreneurs of today or in the past, result from taking that passion and turning it into a reality.

Published in NorthWestern Financial Review January 2018, pp. 35-36. “What bankers can learn from the master of the art world.”